Friday, September 8, 2000 | Los Angeles

Times, www.latimes.com

Exhibition Exposes Attitudes Toward Tradition of Veiling

By ANNE-MARIE O'CONNOR, Times Staff Writer

It is an arresting image. A transparent red veil swirls over a nude woman like a torrent, covering her but revealing the subversive sensuality of her form.

This lush, wall-sized photograph by Shahla Sepehr Bebe--called "Shame"--is among the works of 18 Iranian immigrant artists in a striking Los Angeles exhibition that uses Iran's Islamic dress code for women as a metaphor for their status in society and for universal issues of individual freedoms.

The "Veiling/Unveiling" show at the Eagle Rock Community Cultural Center is certain to resonate in Los Angeles' Iranian community, where some Muslim women adopt the veil voluntarily as an affirmation of their culture.

But for many of the artists--some of whom lived in Iran when women were ordered to wear veils by religious leaders two decades ago, and fired from their jobs or beaten for refusing to do so--veiling is an exercise in forced anonymity. Supporters of Iran's dress code, which dictates that women must cover their hair with scarves and wear long, baggy coats or the more conservative chador in public, point to the Koran's dictate that observant women "draw their veils over their bosoms and not . . . display their adornments except to their husbands."

In one lithograph by Nahid Hagigat, an established printmaker whose work has appeared at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, a woman's animated face fades as she dons a veil and her body becomes an amorphous sphere. A blown-up photographic negative by Santa Monica artist Ali Ahmadpour shows a veiled woman looming like a phantom silhouette.

"Women are reduced to abstract objects by the veil," said Ahmadpour, who left Iran in 1985 and now lives in Santa Monica. "To me, veiling is similar to the Berlin Wall. It is a manifestation of the denial of human rights."

Not everyone looks at veiling the same way, of course, said Elahe Amani, whose drawings also appear in the show. Amani and some other immigrants who were forced to adopt Islamic dress in Iran see the dictates as the most visible manifestation of laws that restricted the rights of women following the 1979 Iranian revolution.

"Veiling should be a personal choice. When it becomes mandatory, you feel imposed upon because regardless of how you feel, you must abide or be subject to arrest and lashing," said Amani, a Muslim-born secular Iranian whose support for the revolution had fizzled by the time she left Iran in 1983.

By contrast, Amani's U.S.-reared daughter, like others of her generation, "sees veiling as a personal preference, as something exotic," said Amani, who is a women's studies professor at Cal State Long Beach and a member of the Society of Iranian Women in Los Angeles, which sponsored the show.

In countries where women are not required to wear a veil, many do so anyway for religious reasons or, in some cases, as a means of projecting a sexless image that allows them to be taken seriously in the workplace, said Cal State Northridge women's studies professor Nayereh Tohidi, who teaches a course on women in Muslim societies. "The new trend is re-adopting veiling to be more mobile in society," she said. "It is to assure their families, I'm not going to be Westernized or promiscuous. But when it's imposed, it's another matter."

Indeed, when Amani attended the U.N. Women's Conference in Beijing in 1995, Islamic Turkish women complained that secular authorities wouldn't let them veil themselves publicly, she said. And Amani's grandmother believed so strongly in veiling that she refused to leave the house for six months in 1936 when the country's leader, Reza Shah, briefly ordered women to stop wearing veils because he wanted to project a more modern image--a controversial episode still remembered as "the unveiling." "Women should make the choice, and that choice may mean wearing or not wearing the veil, or wearing different forms of the veil," Amani said. "I hope this exhibition can stimulate some intellectual exchange."

Curators are counting on it. They are considering hosting debates and forums during the exhibition, which runs through Sept. 30 at the community center, 2225 Colorado Blvd., Eagle Rock. There will even be a journal at a reception Saturday night, from 5 to 9 p.m., for viewers to record their impressions.

f this seems like a didactic approach to art, such polemic forays are common in societies where political turbulence is a fact of life. The artists in the show--one of whom will soon go back to live in Iran--reinvent Islamic religious iconography in much the same way that rebellious young Cuban artists appropriated enshrined revolutionary symbols in Havana in the early 1990s.

Indeed, some of the artists in the show, like Lailah Salartash, a painter who graduated from the University of Tehran in 1997, came of age in revolutionary Iran. They are part of a new wave of Iranian immigrants whose experiences under revolutionary rule distinguish them from the first wave of Iranians to arrive in California, many of whom had ties to the ousted Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi.

Others, like painter Taraneh Hemami, were born in California. Estimates of the Iranian community population in Southern California run as high as 600,000, with half believed to live in Los Angeles County. Hemami, a Bay Area artist whose work has been shown at UCLA's Fowler Museum of Cultural History, makes "sacred books" that mingle memories of her father with grade-school compositions. The books are thickly encrusted with earth, fabric and photographs of bodies that evoke landscapes. Her collages depict what amount to "veiled" men--photos of blindfolded prisoners, lined up in rows, during the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq war.

One of the show's most confrontational works is Ali Ahmadpour's installation piece "Mehrab," named for the prayer niches in Islamic mosques. The niches face Mecca and are often decorated with beautifully ornate Moorish designs. His mehrab, however, is a simple wood cell. A sculpted woman huddles inside on a nail-studded floor. The mehrab is framed by pictures of women--some in modern photographs and others in reproductions of classical Persian art--that are overlaid with traditional religious texts that spell out the restricted role of women in society.

"Whenever there are national problems, Islamic fanatics push women to adopt the [veil] and use them as a scapegoat, but they go after other groups too," Ahmadpour said. "It's like the McCarthy era, when they stirred up hatred of communism and used that to suppress legitimate workers' groups and writers. I really see the veil as a little jail for everyone."

One of the show's major themes, Ahmadpour said, is the concept of identity in his society.

Female literacy increased significantly following the Iranian revolution, he noted. In recent years the women's vote has been instrumental in electing female legislators and the nation's president--Mohammad Khatami, an attendee at the U.N. in New York this week--who has promised reform.

Yet when Iranian religious authorities try to define themselves against the industrialized West, Ahmadpour said, they frequently do so by clinging to outdated roles for women--and by reimposing a dress code that treats their bodies as something that must be concealed.

"Must women be defined so sexually?" he said. "Shouldn't people have the right to define themselves?"

To physician Laila Al-Marayati, past president of the Los Angeles-based Muslim Women's League, the growing commodification of female sexuality in U.S. popular culture is also a demeaning distortion of female identity and may be one factor behind a growing trend of veiling among immigrants to the United States. "I think the whole issue comes down to choice," said Al-Marayati, who is also on the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom established by Congress.Ý"Forcing a woman to cover violates her choice," she said. "But most women who cover by choice are not making a political statement, they're acting out their faith. And they're forced onto a political battleground they don't want to be on. We need to look at deeper issues of discrimination for all women, and women need to come together to fight those things."

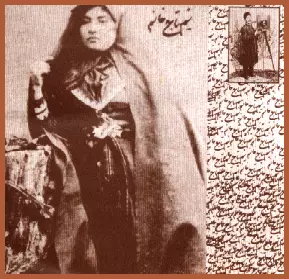

Some of the richest works in the Eagle Rock show grapple with the way that cultural traditions and boundaries are passed down through the generations. "The Inheritance" is a series of black-and-white photographs of Iranian women, taken in the late 19th century, that are incorporated into rich collages of Persian designs and verses of the Koran. The photographs were given to Montreal-based artist Yassaman Ameri by her mother.

Mandis Razavi explores those same generational ties with multiple photographs of men and women in her family, arranged in formal tiered columns that look like a cross between a high school yearbook and the haunting photo lineups of political prisoners that come to light after the fall of repressive regimes.

One photographic installation combines images of veiling--a head scarf, a long coat and a chador to cover the body--with photographs of household objects: a broom, a traditional samovar for serving tea. Next it displays the accouterments of an unveiled woman: a black bra, a black lace shirt--possessions that hint at sexual expression. Mixed in are photographs of prayer beads and verses from the Koran.

Dominating the show is "Shame," the photograph of the nude woman under the veil by Bebe, a photographer who moved to Los Angeles in 1986 and has shown her work in galleries in Santa Monica, Washington and Montreal.

"It is about the shame attached to women's

bodies," Bebe said. "The prejudices against the female form are unchanging,

regardless of whether the government is fundamentalist or reformist. It

is a deeply cultural taboo that we need to address."

Copyright 2000 Los Angeles Times