West Beirut Redux

"Even in the best of times, in the years before the war, Beirut was a chaotic place, its undisciplined traffic legendary. Its various quarters, each with its own character and function, were united by the downtown area at its heart, and all roads ultimately poured into that region. Here was the business center; the head offices of all the major banks, airlines and businesses were all located here. Here also were the specialized markets or souks: the gold market, the fish market, the tailors' market, the glass market, each one an ancient alley radiating away from the center, the palm-lined Place des Martyrs, or, as it was called, the Bourj."

Jean Said Makdisi, Beirut Fragments

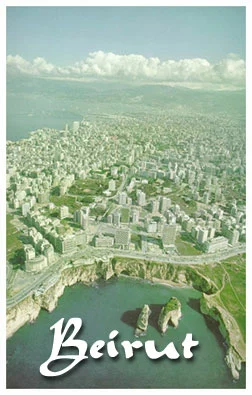

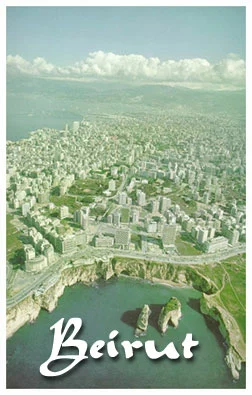

The role of Beirut in the Arab world throughout the 1950's and 1960's was that of a free, cosmopolitan metropolis that was eclectic in its modernity and avowedly secular in orientation. The collapse of Beirut in the 1970's, due to a tragic confluence of political and military factors involving Syrians, Palestinians and, eventually, Israelis and Iranians, led to the destruction of a significant artistic and creative haven in the increasingly reactionary Arab universe.

Ziad Douari's film "West Beirut" provides a tiny portrait of this tragedy. In this finely realized film we have a realistic presentation of a slice of the collapse of this great Arab city.

"West Beirut" begins in a schoolyard. With the children of the French School of Beirut lining up to sing the French national anthem, we find our protagonist, Tariq Nouwari (in English it roughly translates into "The Illuminated Path") seeking to stir up trouble by getting up on the top floor of the school and singing the Lebanese national anthem.

This dichotomy of the national aspirations of the Lebanese, here being played in a joking fashion by a young man who seeks to upend his hated French teacher, against the cultural hegemony of France is more ironic than academic. Throughout the first portions of the film, there are references to French culture which are omnipresent throughout the Lebanese landscape.

But we are quickly ushered into the harsh realities of the war that engulfed this nation, a nation that was created by the imperial authorities to provide a haven for the Maronite Christians who were seen as French proteges. Like the state of Israel to the south, Lebanon began its life as an ethnically particular state. And when it came time for Lebanon to assert its identity in the face of a great political crisis, the collapse was marked by that very religious sectarianism that has marred the landscape of the modern Middle East.

The story of "West Beirut" is told through the eyes of its three young protagonists: Tariq, the wise-cracking young man who looks for the adventure that may be found on the streets of a city that is sub-divided into sections controlled by the various militias associated with the religious and political factions; Umar, Tariq's best friend, a young man who walks the streets with his Super-8 movie camera and chronicles the high- and the low-life of what is happening; and Mayy, Tariq's new neighbor, a Christian girl from Baalbek.

These characters are saturated with the mid-70's culture of the West; Disco music, flared jeans and a general confusion regarding the historical changes occuring in their world. In the decade which followed the twin tragedies of Vietnam and Algeria, the young people of Beirut were left without a real fix on their situation. On the one hand they reveled in the freedom presented by their city, but on the other, the signs of decay burgeoned around them.

In "West Beirut" the streets are a tracherous place. Simply crossing the street or going to the store for a loaf of bread is fraught with danger. Guns are a ubiquitous presence throughout the film. Every two-bit punk who joins a militia can run roughshod through a neighborhood, ostensibly to serve as its "protector."

Tariq's parents, a professional couple, the mother is a lawyer though we are not told the father's profession, are presented as emblematic of what the war was trying to destroy. Like the many novels that have been written about this war (Etel Adnan's Sitt Marie Rose, Hanan al-Shaykh's The Story of Zahra, Ghada Samman's Beirut Nightmares, Elias Khoury's Little Mountain and Jean Said Makdisi's classic memoir Beirut Fragments), "West Beirut" looks at the intimate aspects of the war by providing a lens, the lens of real people who lived their lives throughout this horrible conflict.

Much is made in the film of a famous whorehouse that Tariq accidentally finds himself in after hiding out in a car that drives there. The whorehouse, in the Zeitun section of the city, a section that is a no-man's-land controlled by the roving militiamen, is a sanctuary of sorts. In the whorehouse, the various militiamen and their supporters come to relax and indulge their carnal pleasures. But even the den of sin turns into a den of conflict when the Madame of the establishment finds that one of her "girls" has been killed because she has slept with both a Moslem and a Christian.

At one of the most crucial points in the movie, a line for bread at a neighborhood shop turns into a symbol of what the war has now become for this once-resplendent city: A thug known as the Big Snake cuts through a line of haggard customers who have been waiting all day for a single loaf of bread. The thug demands 20 bags (!) of bread and when the shop owner offers 10, he begins to terrorize him and beat him mercilessly.

It is this image of a young thug beating an elderly man, a man who feeds the neighborhood (and who has just given bread to the thug's own mother!), that is so striking. The passing away of the old order, a world of respect and civilized behavior, in favor of the new order, an order of "get what you can" and disrespect, that has so distorted the lens through which we now see Beirut.

Frequently I am told that the Arab world that our community left in the earlier part of this century is not the same as the one which is situated at the present. In this I have continually balked and said that the world has been transformed by the manner in which the crushing militarization of the region has now engulfed its people.

At the heart of modern Arab civilization is the same value-system reflected by the bourgeois protagonists of "West Beirut." These people are recognizable individuals who in many ways remind me, in their language and manner, of the Syrian Jewish community that I grew up in. Many of the words that can be heard throughout the film are words that we heard spoken in our grandparents' vernacular, words that express a culture that we have been a part of for centuries.

"West Beirut" is a way to see that the particularist elements of modern Arab culture reflect a universalist tendency that can be made to transcend the violence and strife that now unfortunately afflict this region. The values in this film are those of the common individual: Family, the pursuit of individual freedom, finding love and romance and remaining true to one's community in a time of great civil and political strife.

In many of these artistic works we see the Beirutis remaining in their city even as the bombs are falling. They refuse to leave and give into the hate that has overtaken their world. Perhaps this is the most profound lesson that may be learned from such works of art: We must stay the course and not give up on our civilization - even when that civilization looks like it is in the throes of utter destruction.

Ziyad, Tariq's father, while shaving with his son in his bathroom, reviews the familar litany of Arabs about their history. While the Europeans were swinging from tress, the Arabs brought science and philosophy to the world. Tariq then tells his father that such knowledge and culture has vanished. "Look at us now," he says. But the regeneration of this culture, a culture which once included Jews who lived in the Levant, is vital for the health of the region, a region that for many years now has been soaked in blood and tears.

"West Beirut" is a product of the humanist Arab sensibility that sees in human beings the potential for warmth, passion and vitality. With the realities that we now face as ethnic particularism, the bane of modern identity, continues to rear its ugly head, such a universalism comes as a refreshing tonic. It is this cultural pluralism that has nurtured the Levant and must continue to do so in the future if there is to be a peaceful resolution to the many entangled conflicts that continue to infect the region.

David Shasha

Home

Nasawi News Calendar Bulletin Board Poetry Art Links Membership Organization Archive Levantine Project Open Tent